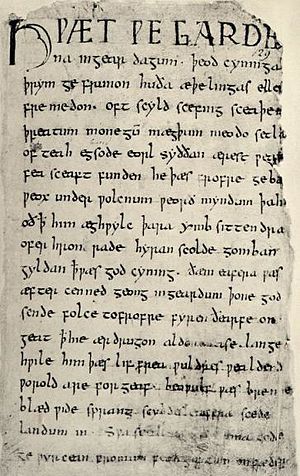

Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia |

| Old English Epic Poem Beowulf |

But how are you to impress upon your fellow human any sense your incredible wit and verbal acuity when you’re umm-ing and ah-ing? Everyone else gets impatient for you to “just spit it out” as you try to remember that really apt word; so eventually you just settle for a less appropriate but still workable word. And that’s the big problem with English: there are just too many words and I (for one) can never remember the one that I really want to use!

I was thinking the other day about the word “fact” - because it sounds a lot like the French equivalent “fait” and I guessed that that was where the English word came from. Actually according to the “Australian Oxford Dictionary

Of course English had its own word for “that which has been done” before it developed its preference for fancy Latin and French words over humble old Anglo-Saxon ones. That is, “deed”. Which if I refer again to the Australian Oxford Dictionary, has an “Old English” origin, “from Germanic: related to DO”. But, you might protest, “deed” doesn’t mean the same thing as “fact” and this is the source of Melvyn Bragg’s effusive paean to “English’s extraordinary ability to absorb [new words]”. Bragg finds that when English absorbs words from another language where a word with the same meaning already exists in English, both words take on a slightly different meaning. Thus “where old English said craft old Norse said skill... in Old English you were sick, in Norse you were ill”. Bragg lauds this habit of adding words to the English “word horde”, describing it as “adding to the richness and flexibility of the vocabulary” as each word takes on a new, more specific meaning, with nuanced distinctions between words, allowing for the expression of more complex and specific ideas.

Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia |

| Influences in English vocabulary |

But to suggest that English has any particular advantage in expressing complex ideas is ridiculous (for one thing it would mean it couldn’t be translated into other languages!). And of course, whilst Stephen Fry might be happy to make outrageous claims on behalf of his beloved language, linguists will have more difficulty in justifying them. The reality, as I investigate my “Larousse de Poche” is that the French word “fait” in fact encapsulates all of the above listed meanings of fact, deed and done - varying according to context.

So, what about the big vocabulary? Is it a bane or boon? Well, for my part, I find it jolly annoying! I can never think of the word with that specific meaning that I’m after. And words with related meanings like “fact” and “deed” don’t in any way hint as to the other’s existence through sounding similar because they have completely alien etymologies. But if you were to ask me which ones I wanted to cull, I could never choose any, because I can’t help but be infatuated with all of the English vocabulary’s richness of connotations. Each word has its own adventure to tell as to how it found itself in our language. Whether it be from the marauding vikings of the Danelaw who gave us “sky” and “knife”. Or if they came from William’s conquering armée who taught the English the hard way about the role of the “state”, “traitors”, “arrest”, “justice”, to “accuse” and “acquit” and to “sentence”, “condemn” and “gaol”. Or the honest “pukka” words from working people under English dominion all over the world whether they be the unsentimental references to pompous “Lord Muck-a-Muck” from those suffering under the thumb of the British Empire, or just the tomfoolery of some “hooligans” in Ireland...

12 comments:

Great article! As I was reading it, I was reminded of George Will, an American whose OpEd pieces are frequently part of our daily paper.

Will seems to pride himself openly on his vast knowledge of language by putting words in his column that require the average reader to run for the dictonary.

Shakespeare said,"Brevity is the soul of wit."

I'm sure Will knows this famous quote, but in an effort to make his readers believe he actually is superior, I'm sure he just forgot it.

Yes! A lovely read best written by an English teacher.

I get the daily Wordsmith emails and only recognize 15 to 20 percent of the daily words. Occasionally, I'll try to use one of the "new" words in conversation and it never works out. I get tired of hearing, "What?"

Yet, every day, I read those emails and try to use the word. Sigh.

Again, lovely writing as usual.

I tend to agree with you. However, in fainess to the Brits, when you speak Australian or American, it ain't right to chicane the King's English. We apologize, Mr. Chaucer.

English is a swine to spell as it is made up of so many influences but tracking down origine of words can be fun and my brother put it quite nicely some people can use the array of words and a lot depends on the context of where he knew someone who would try to show off his vast vocab when a simple statement would do ' t'pub'. Thats something else thats fun with language when you start adding area dialects it really annoys some teachers :)

Such an interesting post, Akseli. Call me a nerd, but English words fascinate me. Sometimes, I like to sip my morning tea and read a dictionary. Or a thesaurus. Embarrassing confession, but true. It helps me on those days when I'm feeling loquacious . . .

Thanks for all of the comments everyone!

Judie, when you describe Will, I can tell exactly what type of writer you mean.

PAMO, Yes, sometimes some words are best kept for internet posts. People can address their "whats" to Google that way.

JJ, hasn't it been the Queen's English since 1952? But yes, I suppose you're right. Does it make any difference if we've got the Queen's head still stamped on our coins?

Chibi J. I know exactly what you mean. I have a cousin who has a grand proposal for "spelling reform" that would do away with all of the interesting spellings from different countries. But I think it would be an incredible shame. Unfortunately Australia doesn't really have dialects - but I did grow an appreciation for your very many when I was over your way last year.

Roxy, I think in the blogging world, you're in safe company calling yourself a word-nerd!

I am always fumbling for the right word! But then again, I struggle just to remember the person's name I'm speaking to, let alone the best way to express what I'm trying to say. That's the curse of knowing, on some subterraneous level, so many words- we know there is a better one, somewhere. Often I simplify it to something stupid so as not to lose the person while I'm trying to think. That's why I like to write, I guess. It gives you time. I was thinking the other day that words, as many as there are, are really such an imperfect medium. Despite what a wonderful tool they are for connecting with one another, I don't think we can ever hope but to come close, at best, to what we are really trying to communicate. Sorry, just doing some deep thinking lately on the subject. I heard a song called "Words" just last night... interesting.

When I first encountered Heidegger during my time studying philosophy over thirty years ago, I remember being very irritated at his claim that the two best languages for expressing oneself clearly were Ancient Greek and German.

Having lived in Germany for nearly twenty five years now, I appreciate the point he was making a little more. In German you can actually construct words by combining prepositions and roots to express exactly what you want to say, whereas English will generally avail of Greek or Latin roots - or take something else entirely!

But, on the other hand, that's part of the joy and spontaneous poetry of a living language. Although I am now functionally bilingual, I can't imagine writing in German; not for fun at any rate - work is a different matter, where I have to write lots of German.

In my particular case, where days frequently go by without speaking a word of English, another aspect comes into play. I often find myself just slightly "distanced" from my native language - something which I sometimes think helps me to reflect more on exactly what I write. In moments of creative megalomania I sometimes wonder if this was the case for Joseph Conrad too ... :-)

Karyn, I agree. Writing's much easier - you can delete all of that umm-ing and ah-ing. Plus, you can cheat by writing things like "verbose" and "synonym" into Google!

Francis, that's an interesting point. Although, I'm not very familiar with German I had heard that the language had a famous facility for coining new words. Like the much over-quoted "schadenfreude". But, I also get the impression that, perhaps for the same reason, German can be difficult to read when translated into English. Or maybe it's just the German works that get translated into English: Heidegger, Hegel, Marx, Einstein?!

Akseli, German texts (particularly academic ones) can be difficult, even when they are translated into German!

There's a story told of a (German) colleague of Heidegger who claimed that he used to wait until the master's works were translated into English before reading them; that way he could be sure that at least one person had understood them!

Beautifully written. I agree, words are an adventure. And I like the idea of a Viking sky. Guess I'm a bit of a comiconomenclaturist who enjoys a hippopotomonstrosesquipedalian word every now and aagin...

Francis, that story is definitely worth retelling. I'm going to remember it.

Snyder, I was also surprised to find out that a word so fundamental as sky actually came to English from old Norse. And I might steal one of your hippopotomonstrosesquipedalian words for future use.

Post a Comment