|

|

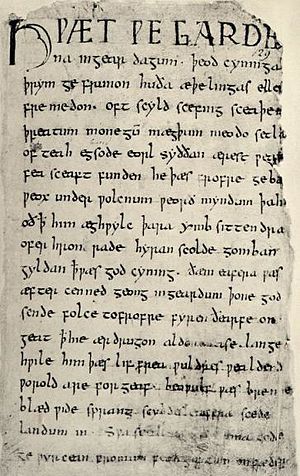

| Old English Epic Poem Beowulf |

I’m a great fan of Melvyn Bragg’s “

The Adventure of English

”, but there is one part in his series when he is waxing lyrical about the uniqueness of English and it’s large vocabulary and extensive loan-words and I can’t help thinking that he’s making a virtue out of a necessity (or at least a virtue out of an indifferent fact). Because, really, is the English language’s much-vaunted big vocabulary actually as good as all that? I know it’s good in a social setting when you want to show off your … you know show off your... not lexicalness... logicalness? no.... Oh what’s that word?! Loquaciousness! Loquaciousness that’s it!

But how are you to impress upon your fellow human any sense your incredible wit and verbal acuity when you’re umm-ing and ah-ing? Everyone else gets impatient for you to “just spit it out” as you try to remember that really apt word; so eventually you just settle for a less appropriate but still workable word. And that’s the big problem with English: there are just too many words and I (for one) can never remember the one that I really want to use!

I was thinking the other day about the word “fact” - because it sounds a lot like the French equivalent “

fait” and I guessed that that was where the English word came from. Actually according to the “

Australian Oxford Dictionary

” it comes from the Latin word “

factum” which just like in French is the past tense form of the verb “

facere” (“

fait” and “

faire” in French) “to do”. Which is to say that really a

fact is simply a

done - something that has been done. The etymology is easy to follow in French and Latin, but in English it’s not at all readily apparent that the word “fact” is related to the word “done”.

Of course English had its own word for “that which has been done” before it developed its preference for fancy Latin and French words over humble old Anglo-Saxon ones. That is, “deed”. Which if I refer again to the Australian Oxford Dictionary, has an “Old English” origin, “from Germanic: related to DO”. But, you might protest, “deed” doesn’t mean the same thing as “fact” and this is the source of Melvyn Bragg’s effusive paean to “English’s extraordinary ability to absorb [new words]”. Bragg finds that when English absorbs words from another language where a word with the same meaning already exists in English, both words take on a slightly different meaning. Thus “where old English said craft old Norse said skill... in Old English you were sick, in Norse you were ill”. Bragg lauds this habit of adding words to the English “word horde”, describing it as “adding to the richness and flexibility of the vocabulary” as each word takes on a new, more specific meaning, with nuanced distinctions between words, allowing for the expression of more complex and specific ideas.

|

|

| Influences in English vocabulary |

But to suggest that English has any particular advantage in expressing complex ideas is ridiculous (for one thing it would mean it couldn’t be translated into other languages!). And of course, whilst Stephen Fry might be happy to make

outrageous claims on behalf of his beloved language, linguists will have more difficulty in justifying them. The reality, as I investigate my “

Larousse de Poche” is that the French word “

fait” in fact encapsulates all of the above listed meanings of fact, deed and done - varying according to context.

So, what about the big vocabulary? Is it a bane or boon? Well, for my part, I find it jolly annoying! I can never think of the word with that specific meaning that I’m after. And words with related meanings like “fact” and “deed” don’t in any way hint as to the other’s existence through sounding similar because they have completely alien etymologies. But if you were to ask me which ones I wanted to cull, I could never choose any, because I can’t help but be infatuated with all of the English vocabulary’s richness of connotations. Each word has its own adventure to tell as to how it found itself in our language. Whether it be from the marauding vikings of the

Danelaw who gave us “

sky” and “

knife”. Or if they came from William’s conquering

armée who taught the English the hard way about the role of the “

state”, “

traitors”, “

arrest”, “

justice”, to “

accuse” and “

acquit” and to “

sentence”, “

condemn” and “

gaol”. Or the honest “

pukka” words from working people under English dominion all over the world whether they be the unsentimental references to pompous “

Lord Muck-a-Muck” from those suffering under the thumb of the British Empire, or just the tomfoolery of some “

hooligans” in Ireland...